We have recently wrote about the respiratory system: from the upper respiratory airway down to the primary respiratory muscle, the diaphragm. But what about the protective rib cage? Our ribs play a critical role in not only respiration, but in movement, too.

Let's get a better handle on our ribs.

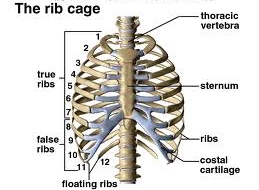

Rib facts:

- There are 7 sets of true ribs, ribs 1-7

- There are 5 sets of false ribs, ribs 8-12

- Rib sets 11-12 are considered floating ribs

- Ribs move when we breath

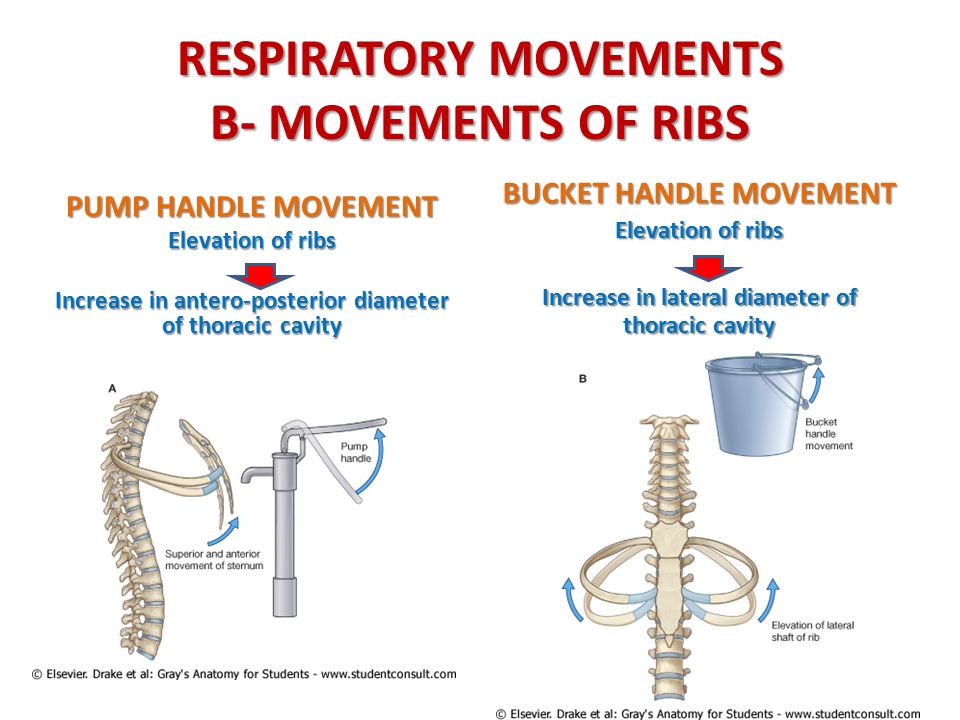

- The true ribs are dominated by a pump handle action

- The false ribs are dominated by a bucket handle action

Understanding Fact #1

The first 7 sets of ribs directly attach to the sternum anteriorly and to the thoracic spine posteriorly. This forms a singular unit that is stable and rigid. While this helps to protect the heart and lungs, its' position and motion will dictate the function and orientation of the scapula as well as influence apical lung expansion.

Understanding Fact #2

Rib sets 8-10 are considered false ribs. These ribs have a posterior attachment to the thoracic spine, but anteriorly they only connect to the sternum through costal cartilage. This makes them more mobile than the true ribs and allows them to be influenced by our abdominals. Our abdominals help the ribs facilitate the respiratory function of the diaphragm. This is reflected in the infrasternal angle (ISA). A normal ISA is about 90 degrees, if wider, greater than 100 degrees, it indicates poor abdominal opposition and a diaphragm posturally orientated. If less than 90 degrees, there is likely an abdominal imbalance driving a similar diaphragm orientation.

Understanding Fact #3

Rib sets 11-12 are also false ribs, but classified as our floating ribs. These ribs attach posteriorly to the thoracic spine, but do not have an anterior attachment. These ribs do not serve a significant role in the respiratory process, but are critical for protection of vital organs like the kidneys and the adrenal glands.

Understanding Fact #4-6

Facts 4-6 are all about normal rib mechanics during respiration. As we breathe the ribs have to move in such a way to optimize thorax expansion. All ribs upon inhalation will externally rotate and elevate, anteriorly, and internally rotate and depress, posteriorly. The opposite occurs during exhalation. However this is only part of the story for optimal thorax expansion. The rest of the story is found at the thoracic spine.

The orientation of the costovertebral joints are different for the upper and lower ribs. As a result the defining motions within these ribs also differs. The movement of true ribs can be best seen from a lateral view and resembles the motion of a pump handle. Whereas the false ribs have more of a bucket handle motion and can be seen posteriorly. These normal mechanics both work to best increase the thorax dimensions during inhalation and decrease it with exhalation. This in turn creates a pressurized system that will drive bidirectional airflow.

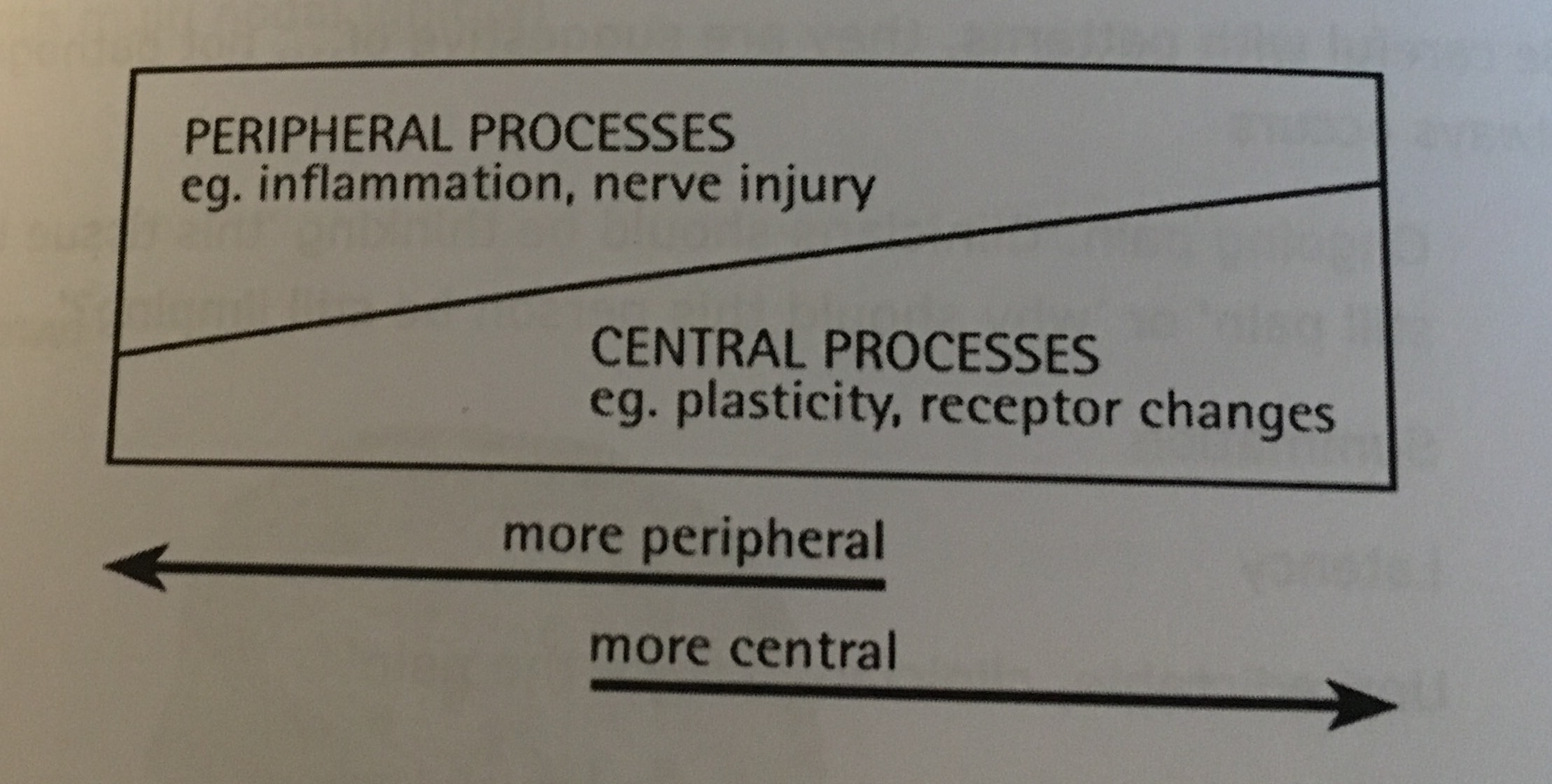

But how does this influence our movement?

Our movement is dependent upon how we manage this pressure system. You see, as the arms and legs move, they will change the shape of the thorax and alter the airflow as well as the pressure within it. As the thorax shape changes so does the orientation of our pelvic innominates and scapulae. So if we have poor rib mechanics or don't manage our thorax pressure well we will begin to compensate and restrict our movement patterns. Thus it becomes increasingly important to be good pressure managers to avoid these compensatory movement strategies.

The ribs have become vastly under appreciated in our movement health. They can and do influence multiple body parts as well as systems making them an ideal starting point for almost every injury type. Hopefully you can appreciate this and now have a better handle on why our ribs matter in the restoration of our movement health.

Stay Well, Stay Strong

Keaton

References:

- Hartman, Bill, ALL GAIN, NO PAIN: The Over-40 Man's Comeback Guide to Rebuild Your Body After Pain, Injury, or Physical Therapy. William Hartman. 2017.

- Lee DG. Biomechanics of the thorax - research evidence and clinical expertise. J Man Manip Ther. 2015;23(3):128-38.

- Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation. Mosby; 2010.