In Parts 1 and 2, we discussed the relationship between the airway and stress on the body and how the upper airway plays into that. In this article, we will discuss the prime mover of the respiratory system, the diaphragm. The diaphragm muscle is especially important, not just because it keeps us alive but also because we use it roughly 25,000 times per day. It then becomes important to know how it functions, and this requires an understanding of anatomy. Here’s a few important facts about the anatomy of the diaphragm:

The right half of the diaphragm (hemi-diaphragm) is larger, thicker and stronger than the left.

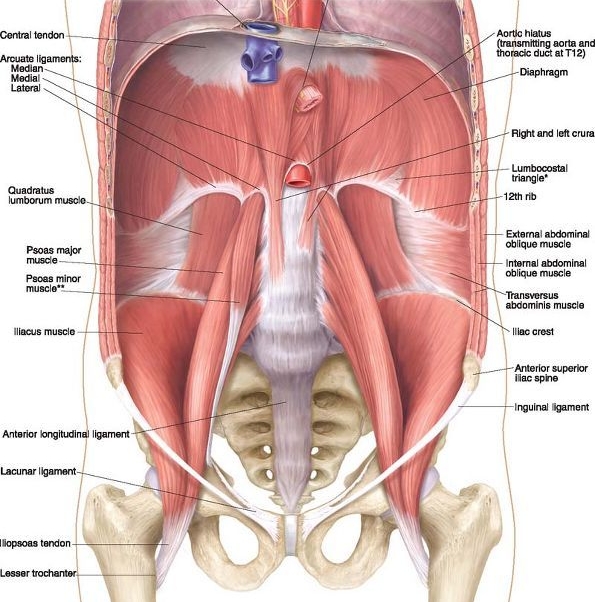

The crura (“legs”) of the diaphragm attach to the bodies and disks of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd lumbar vertebrae on the right and the 1st and 2nd on the left.

The medial ligaments of the diaphragm cross over the psoas, a muscle which has a hip flexor function.

The position of the right hemi-diaphragm over the liver assists in keeping the right side in its resting domed shape whereas the position of the left hemi-diaphragm under the pericardium assists in keeping the left side in its flattened descended active state.

The arcuate ligaments of the diaphragm on the lumbar spine can act to “tighten” the back into an arched and loaded position.

During inhalation, the diaphragm descends into a “flattened” shape and during exhalation the diaphragm forms into a domed shape allowing airflow.

A few things that we can learn about function of the diaphragm based off of these facts is that the diaphragm is a muscle with a stronger pull on the right. This means as we breathe 25,000 times per day we may be cranking the spine to the right. The diaphragm is also an important muscle in regards to posture. If the abdominals, especially the internal obliques and transverse abdominus, become weak, the diaphragm may stay descended on both sides into a “flat” and shortened state resulting in potentially tight backs and hip flexors. When this occurs the diaphragm will assume a more postural stabilizing role rather than its desired respiratory role. We may also notice rib flares, especially on the left due to the position and asymmetry of the diaphragm. This shortened state of the diaphragm makes it weaker as a respiratory muscle because it lacks a normal length tension relationship. Because of this we may end up using accessory muscles of the back and shoulders to inhale which may result in tight shoulders and necks. Though this doesn’t sound like it should be a problem because you’re just breathing, but you’re doing it 25,000 times per day!

This strongly relates to stress. The resulting decrease in intra-abdominal pressure results in a “hyper-inflated” state. This can lower the CO2 in the body which increases the “fight or flight” response resulting in an increased breath rate at rest. This can also restrict blood flow to the cerebral cortex of the brain, impair gastrointestinal blood flow, promote fatigue and weakness, increase sympathetic adrenal activity, increase anxiety, as well as make you more sensitive to light and sounds. Like we discussed in Part 2 these are all strongly associated with mouth-breathing.

Now that we’ve seen what inefficient breathing looks like at rest, let’s look at optimal mechanical function of the diaphragm and how a physical therapist can help you out in this regard.

Optimal mechanical function and power of the diaphragm occurs when the diaphragm is able to go in and out of its resting domed shape and flattened active state on both sides and even be able to alternate in the appropriate conditions. The diaphragm is mechanically coupled with the abdominals and the rib cage and these all depend on each other for optimal function. This relationship is referred to as the “zone of apposition.” Abdominal disuse can result in flared ribs and a loss of a zone of apposition. This may appear as “belly breathing.” There’s nothing wrong with belly breathing however if this is the preferred way of respiration, the result can be an elevated stress response and the development of pain syndromes. A physical therapist can help you to restore a zone of apposition by helping you to normalizing resting abdominal tone thereby increasing intra-abdominal pressure and allowing the diaphragm to rest in its domed shape. In this shape, the diaphragm will function with the abdominal musclature in a piston-like movement allow us to avoid overextending and tightening up the lower back. In turn, this will end up relaxing accessory breathing muscles throughout the body: back, shoulders, and neck. Hence, how you breathe matters, especially since we do it 25,000 times per day!

As always, take care, and breathe easy!

Dave

References

Postural Respiration: An Integrated Approach to Treatment of Patterned Thoraco-Abdominal Pathomechanics. 2000-2016.

Boynton B, Barnas G, Dadmun J, Fredberg J: Mechanical coupling of the rib cage, abdomen, and diaphragm through their area of apposition. J Appl Physiol 70:3,1991.

Cassart M, Pettiaux N, Gevenois PA, Paiva M, Estenne M. Effect of chronic hyperinflation on diaphragm length and surface area. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 156:504-508, 1997.

Estenne M, Derom E, DeTroyer A. Neck and abdominal muscle activity in patients with severe thoracic scoliosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Aug;158 (2):452-457.

Goldman M, Mead J: Mechanical interaction between the diaphragm and the rib cage. J Appl Physiol 35:2,1973.9.Hodges P, Gandevia S, Richardson C: Contractions of specific abdominal muscles in postural tasks are affected by respiratory maneuvers. J Appl Physiol 83:3, 1997.10.

Hruska RJ: Influences of dysfunctional respiratory mechanics on orofacial pain. Dent Clin North Am 41:2,1997.